Before Justice: Meister's Legacies of Critique

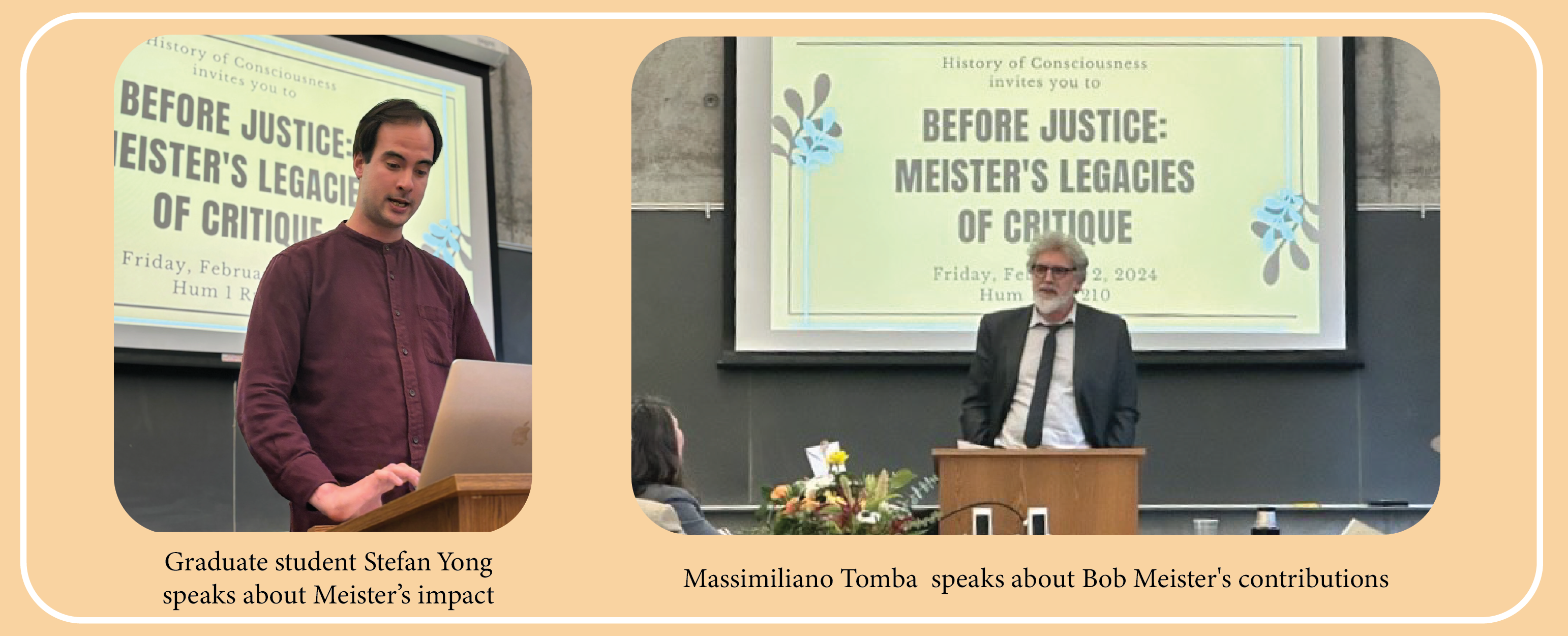

On February 2nd, 2024, the History of Consciousness Department marked Professor Bob Meister's 50th year of teaching at UC Santa Cruz with an afternoon of discussion reflecting on Professor Meister’s research and academic contributions. Affectionately called Meisterfest, Before Justice brought together colleagues, interlocutors, and current and former students to reflect on Meister's impacts on their personal lives and professional careers. Included below are the words of a few of the speakers at the event.

Image Gallery

Select Talks

Still about the Jews: Some Remarks on 'After Evil' - Daniela Tolchinsky

Meister Controversy - Jack Davies

Still about the Jews: Some Remarks on 'After Evil'

Daniela Tolchinsky

When I arrived at UChicago as an undergrad in 2011, Transitional Justice was the next big thing. In classes on the subject, I was told over and over again about how these processes made real change but could be improved upon, and we, in the classroom, were thinking through how to do that. There were big questions still open within the field, I was told: whether trials or amnesty better yielded democratic stability. Whether the guchacha courts in Rwanda could be adapted and replicated in other local contexts to achieve similar results.

These questions didn’t feel quite “big” to me, given the enormity of the politics that had preceded democratic transitions. They felt radically insufficient to, for example, address the gaping fact that the United States had intentionally propped up and backed the military dictatorships that had just ended. And that now, the United States now being upheld as the gold standard toward which these post-dictatorship countries were to strive. Something about that didn’t square. And my teachers’ questions about amnesties vs trials seemed to miss that mark.

Of course, I had no language through which to describe this confused instinct. Until I got to a course called After Evil.

Bob’s argument in that book is that Human Rights Discourse (HRD) is, on a deeper level, about the continuation of a counterrevolutionary project, where beneficiaries of historical injustice get to keep their unjustly won gains. The argument resonated with me the moment I encountered it – I read the book in its entirety three times that year, struck by the layers (and stuck in the density) of Bob’s argument. I’d finally encountered someone asking questions about the water in which we were all swimming, as if Bob was able to observe it from without – like amidst a sinking Titanic, he’d created a life raft from which he could see and describe that a ship had hit an iceberg. This book pointed out what seemed almost obvious after reading it, but what, until reading it, had been impossible to see. And Bob invites his readers to join him on that life raft. Reading this book was like been thrown a buoy so I could emerge for a moment and take a look and what was going on around me. In Bob’s language, the confession of his critique instantly converted me.

After Evil pulls its readers out of a muck that we’re largely still stuck in. Returning to this thirteen-year-old book in anticipation of today’s event reminded me how enormously relevant it still is, in the midst of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. It’s done more to ground my understanding of what’s happening right now than almost anything else I’ve seen published in recent months. So, I want to spend a few minutes today bringing your attention to specific parts of Bob’s argument. Maybe it’ll throw you all the life raft this book threw me.

I’ll begin by summarizing the book’s overall view: After Evil claims that Human Rights Discourse (or, HRD) – whereby the past is deemed evil so evil can be put in the past and we can universally enter a time characterized by delaying a just future – that all this is largely based on the Jews. Human Rights Discourse begins with the claim that there is nothing worse than what happened at Auschwitz –that there’s nothing worse than the bodies in pain experienced there. After Auschwitz, every future atrocity is (to be experienced as) a repetition of that atrocity, like a trauma we must anxiously remember not to forget, so it doesn’t reemerge in the future. The logic of this way of thinking is encompassed in the phrase, “Never Again.”

To learn the lessons of Auschwitz so we can defend against its return, we’re all asked to internalize the experience of those who were there: the traumatized, victimary, survivors who remember and are haunted by what happened (epitomized in figures like Elie Weisel). In this respect, HRD rests on universalization of Jewish survivors – and Jews are meant to embrace their own universalization. They are enlisted to, one might say, traumatize us at one remove, in order to teach the world to live by an ethics of “never again.”

We, in turn, are asked to feel bad – or, suffer at one remove – every time another atrocity happens, to show our moral alliance with victims/survivors. In this way HRD teaches us to feel bad about others’ suffering, but in a good way. When the original suffering happened (as if Auschwitz was the first time) we didn’t know to feel bad in time. Now that we know to feel bad, we feel good about it – not because our compassion makes future suffering less likely, but because it shows we’ve learned our lesson – we’ve morally converted.

Through this moral conversion, Bob teaches us, everyone is brought into a new kind of time, one characterized by the non-immorality we display when we feel bad for suffering others. Bob points out again and again that this stance is distinct from both the immorality of the past, and the imagined justice of the future. The temporal point here is that the present isn’t just or ethical, it’s just not-unjust. That in the present, we delay and push off any sort of justice by instead resisting the return of past injustice.

Now, that alone is a novel and profound argument. But Bob takes it much, much further in connecting HRD’s temporality and ethics to its politics. He discusses the numerous implications of this view - from South Africa to the US war on terror and history of racial enslavement. I want to draw out 3 specific implications here today. I chose these three because they inform much of my own work about Israel, Palestine, and the Jews. And, in the context of Israel and Gaza, I think they’re important and illuminating:

I’ll begin with the first point: By engaging the theological register, Bob shows us how HRD implicitly imagines a world without Jews. As we’ve noted, HRD universalizes Jewish suffering – Jewish suffering is supposed to teach the world the meaning of all suffering: or, rather, that all suffering is meaningless, and constitutively unjust. In other words, Jews hold the key to this whole project, because it’s based on their universalization. The Jews, then, must continue to exist as Jews, but only for everyone else’s sake. In a philo-Semitic shift, the Christian West now requires that Jews live alongside Christians, taking part in a new, joint project of being against suffering. In other words, due to the now-universal significance of their past, Jews remain necessary in the present.

Bob teaches us that this move is distinctly theological – HRD uses the Jews in a way that is structurally similar to how Saint Paul did, back when Christianity first superseded Judaism in the first century.

“(Paul’s was a) redescription of Christianity itself as a Judeo-Christianity that continues and supersedes the distinctive features of Jewish suffering by allowing everyone to claim them.” Paul’s point was that Jews must survive for now, until Christ’s second coming when everyone (Jews included) either converts or dies. The eventual goal of Paul’s Judeo-Christianity is thus for Jews to disappear under the banner of Christian, messianic universality – but not yet. Until then, we live in a Judeo-Christian time when the two religions coexist, but with the underlying assumption that one, eventually, will not exist, because when we’re ready for a future of messianic justice, Jews will no longer be required to teach us lessons about the past.

In this sense, the “just” future HRD imagines and suppresses (by delaying it), “is ultimately about the destruction of the Jews as such… Assimilation through hyphenation constructs the present moment as a step toward a world without Jews” while in the present we, a) refuse to take that step, but b) implicitly envision that step as both immanent and positive. This bears important implications for our contemporary politics: Minimally, it helps explain why some of our culture’s biggest antisemites are also the biggest supporters of Israel, the state whose supposed purpose is to protect the Jews – keeping them alive “in the meantime,” until a messianic moment of justice to come.

The second criticism of HRD is that its universalization of Jewish suffering means that “everyone who claims political high ground is also claiming to be… the authentic claimants to the grievances traditionally raised by Jews.” If Jews’ immutable role is to teach the world that all suffering is like Jewish suffering at Auschwitz, the only way we now recognize suffering is by comparing it to Jews’ – specifically, to the Holocaust. It means that no other groups’ suffering is internally self-legitimating or authentic in the way Jews’ is.

This is true most recently for Jews’ own victims in Palestine. In South Africa’s case against Israel at the Hague just last week, they allege that Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza – this is, of course, the crime whose prototype was done to the Jews. Ironically, South Africa did not come to the Hague alleging that Palestinians are subject to apartheid – a claim that is equally (if not more) justified. But the apartheid claim would have been based on South Africans’ own past suffering, rather than Jews’ past suffering.

After Evil allows us to see that South Africa’s choice to claim genocide instead of apartheid isn’t merely due to the inherent force of one claim over the other – it’s also a qualitative decision rooted in the paradigmatic role of universalized Jewish suffering in our world, and especially in global human rights law. It shows that all suffering – including the suffering Jews inflict – is only made legible by comparing it to the suffering Jews experienced. If that’s the case, Bob has helped us see how we’ve put Palestinians in a doubly difficult position.

The final problem arising from HRD that I want to emphasize, is that it produces a dual Jewish exceptionalism: Jews become both exceptionally culpable, and exceptionally innocent at the same time.

On the one hand, Jews are uniquely redeemed in advance, for any victimizing they might do. As the group who’s needed to teach the world to be against suffering, anything Jews do to protect themselves is inherently legitimate. And anything the Israeli state does is filtered through the lens of universally necessary, Jewish self-preservation. Here I’ll quote from Bob at length:

“The notion that Israel, as a state… seeks only the military security of post-holocaust Jewry, presents Israel’s security itself as having a redemptive (messianic?) significance for the post Holocaust world… [This is] the foundational paradox of Human Rights Discourse itself - the reason that Israel must, ultimately, be supported, even by its humanitarian critics, no matter what it does… Were Israel’s friends to ‘abandon’ it merely because of something it did, so the argument goes, it would be forced to become Kahanist in order to prevent another Holocaust.”

Bob is saying that if Jews are necessary for the world’s redemption, we can’t blame them for anything they do in service of their own self-preservation. They can’t be understood as aggressors, because any attack the Israeli state perpetrates is ultimately about protecting Jews. After re-reading this, I couldn’t help but recall President Biden’s insistence, after October 7th, that only staunch support of Israel would enable him to pressure the Israelis down the line. Bob’s point here teaches us why we will not arrive “down the line” – because Israeli security itself is redemptive for HRD, it will always be prioritized.

On the other hand, HRD opens the door to a new crime that Jews can uniquely commit. If Jews refuse to universalize themselves, they block the whole project of HRD from unfolding. Jews can be blamed for avowing only their own suffering in the present - for failing to promulgate the notion that now everyone/anyone is (like) the Jews (or morally equivalent to the victimary figure of a Jewish survivor). Again, I’ll quote at length:

“In a world that has learned to feel good about itself by feeling bad about the Jews, one can take special umbrage at Jews who refuse to apply the Holocaust’s lessons to their own treatment of Palestinians. These Jews are to be criticized for thinking that they are the only real Jews, and that the Holocaust confers special privilege on actions they take… This attitude has become a seemingly new offense that Jews, and Jews alone, can commit now that their victimary identity has been universalized.”

This means that when Jews produce their own victims, they are doubly culpable in a way the rest of the world isn’t. As the original victims who are supposed to teach the world not to victimize again, their breach of this lesson uniquely stops its global proliferation. For Jews to cause suffering to Palestinians, or worse, to refuse compassion for Palestinian suffering, isn’t merely a failure to feel another’s pain: it signifies Jews’ refusal of their own universality, thwarting the (Pauline) project of Judeo-Christianity as a whole.

All in all, Bob’s work in After Evil enables us to see that our present-day political discourse, in the United States especially, is preoccupied with two versions of the same claim: Both say, “Never Again is Now,” as I’m sure you’ve noticed walking around campus or perusing social media. Our politics are enveloped by two sides protesting each other, and both their signs bear this identical slogan. One side, though, means “never again will Jews suffer.” And the other means “never again will anyone.” The logic informing both is the same.

What Bob’s book uniquely allows us to ask is, why is that the only thing we can say? Who might dare to say something else? And what else can we imagine they might say? On the 118th day of bombing, these questions could not be more urgent. I am profoundly grateful to Bob for enabling us to ask them.

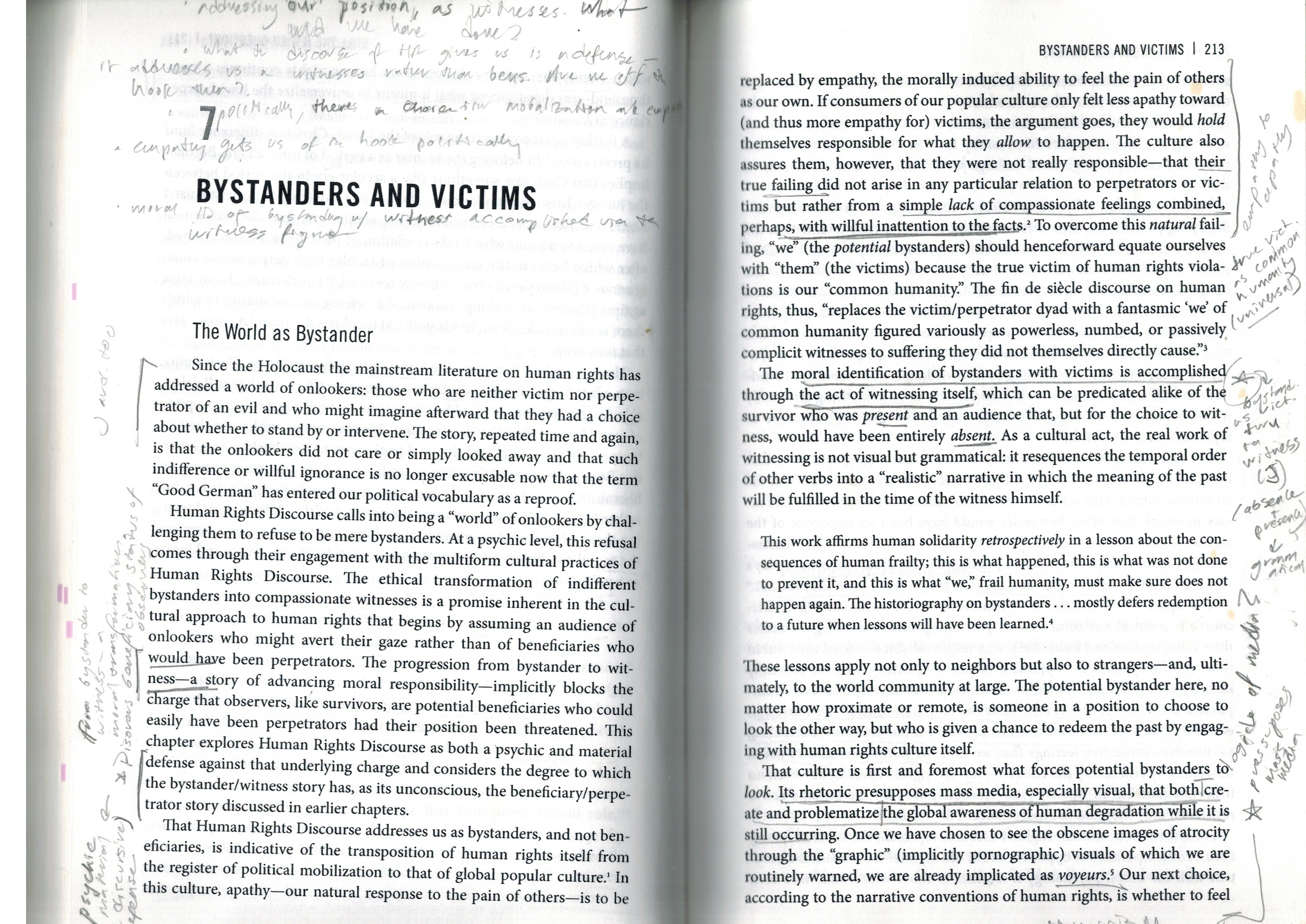

Annotated page from Meister's After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights (2011), courtesy of Isaac Blacksin

Annotated page from Meister's After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights (2011), courtesy of Isaac Blacksin

Jack Davies

The task of my contribution is to pivot us from these fascinating discussions of Bob’s work, and towards the more celebratory portion of today’s programme. It is called, “The Meister Controversy.”

In February 1970, amid roaring campus protests, E. P. Thompson published an article in New Society titled, “The Business University,” and shortly afterwards, a book called, Warwick University Ltd. Here, Thompson memorably proposes that the causes of student uprising and suppression at Warwick lie neither in the inherent irrationality and immaturity of students, nor in the irredeemably out-of-touch attitudes of stuffy British administration. His alternative, “which most observers,” he wrote, “would overlook as being too improbable,” is that dominant elements of the administration had become so enmeshed with industrial interests that they had wrested the function and purpose of the university away from its normative values and towards those of business management. Such a dynamic could plausibly cause student revolt of the kind then unfolding, of which he wrote:

If such a revolt were to occur, then the position of the university teacher would seem to be clear. He could not confine his role to that of making clucking ‘protective’ noises on behalf of the rights or good intentions of his students. As an intellectual worker, in whatever field of study, he must be unconditionally opposed to the mystification of the truth. He could no longer, by his silence, assist in the mystification of the very institution in which he and his students work. He should come to the side of the students by telling them what he knows of the truth.

In October 2009, 40 years later, Bob Meister published a series of open letters to UC students bearing the title, “They Pledged Your Tuition.” You all now, with enormous thanks to Won Jeon and Jess Fournier, possess printed copies of these letters. In these, Bob leveraged his dual position on the Committee on Budget and Planning and his position in the faculty union to first obtain and then to expose, with relative impunity, the details of UC’s plan to diversify out of the education business.

Thompson’s intervention was undoubtedly important at the time he made it, as is clear from many fond recollections. But today, a half century since his article and since Bob’s appointment to UCSC, there is an almost quaint quality to Thompson’s critique. Far from being “almost too improbable to consider,” the fact that the university is a business, or has abiding business interests, is for us almost too obvious to bear saying. It is, at times, freely admitted or even worn as a badge of honour—as the responsible attitude of an administration facing state budget cuts.

We might explain this quaintness by the 50 ravenous years of neoliberal statecraft and its seeping ideology—that what was an almost inadmissible proposition in 1970 has become common sense. But Bob’s work on financialization, and especially his activism in the university, helps us to see rather more than this: namely, that UC had begun hedging its portfolio after realizing that it was over-exposed to the business of educating Californians. This indexes rather deep transformations in the structure of capital accumulation across this historical period, of which Bob must be considered a major theorist.

Just a generation or two ago, a UC degree, on average, put its holder in the top 20% of earners in the state, and therefore, at that time, on the upside of widening income inequality. It paid to get a UC degree. Since then, with almost all income gains concentrated in the top 1%, the benefits of investing in a UC degree for students have dwindled considerably, precisely as its cost, in terms of tuition and housing, have risen steeply. This is to say nothing of changes in the quality of a UC education, measured in such non-pecuniary terms as instructor-to-student ratios.

As Bob contends, this, to UC’s Regents, looked like a pretty grim business model. They needed to diversify out of education and into such sectors as construction, real estate, insurance, and end-of-life care, especially with the ever-looming prospect of further state budget cuts in the ever-probable event of financial crisis.

It is, thankfully, illegal for UC to use funds from either the state or from tuition fees for anything unrelated to its educational mission. Now Bob, with access to the documents and with protections under labor law, could explain to his students in the UC that their tuition had been pledged as collateral on the Regents’ “General Revenue Bonds,” whose funds had no such stipulations.

This was especially great, because they could leverage significantly more by pledging the tuition receipts on bond markets than they could have hoped to invest directly, were this permissible. The bond markets, that is, loved this type of collateral, because the tuition flowed in regularly and reliably, and UC could always raise tuition. The market rewarded the Regents with sensationally low interest rates—much lower, indeed, than those paid by students on their loans—and they became one of the leading municipal bond issuers in the United States. As Bob put it, they were therefore able to go on a building spree while blaming a budget emergency for cutting back on instructional quality.

A public school like the UC, developed to educate the generations of Thompson and Meister and prepare them for good jobs, was now diversifying out of the education game in order to provide the likes of Thompson and Meister with end-of-life care in private hospitals—financed, ultimately, by the compounding, semi-private debt of millennials and zoomers.

Like Thompson before him, Bob’s activism was part of, and helped to catalyze and deepen, a wave of student protest and building occupations. From all reports, Bob was very active during the student movement at UC against tuition hikes, discoursing on the bullhorn at occupations as he would 12 years later at our picket line. He was also denounced publicly by UC administrators in writing and on television. You can read about this in several places, including a brand new Duke collection, to which Bob contributed a chapter, “Confessions of an Accused Conspiracy Theorist.”

The concrete achievement of this movement was the freezing of tuition for a decade, although it took longer than that to impose hikes, which are landing right now. The reason for the delay owes to a rather remarkable coincidence, although I expect Bob, our resident conspiracy theorist, sees something rather more than coincidence at play.

I refer to the UC Regents meeting of January 2020 in San Francisco, which was slated to discuss raising tuition ten years on from the Meister Controversy. This meeting happened to fall in the month between the start of a wildcat grade withholding strike at UCSC in fall 2019, when I was Bob’s TA for Introduction to History of Consciousness, and our later full work stoppage in February 2020. We were demanding what we called a COLA, a cost of living adjustment that would index our wages to the rental market, and thus keep us out of rent burden, defined as spending 30% of one’s income in rent.

The system-wide service worker union, AFSCME 3299, had been out of contract for years, and its K7 skilled craftsmen unit at UCSC had initiated an open-ended strike in the electrified milieu of our wildcat action.

So, holding the missing grades of Bob’s students, I headed up to SF with hundreds of UCSC colleagues, and hundreds more AFSCME workers, officials, and student supporters from various northern campuses. The Regents wisely considered that this context was hardly propitious for a discussion of hiking tuition, and tabled that item.

Our own wildcat strike played out in often chaotic ways, leading to many threats, several arrests (including some of Bob’s students), dozens of firings (including more of his students), and bled into the pandemic shutdown. We had some partial wins, innovated and honed our strategy, won our jobs back, and concluded a second strike at the end of 2022, this time UC-wide.

The next stage, before us now, returns us to the world of UC’s fiscal and financial strategies in the form, for one example, of UCSC’s “Fresh Air” budget program—every bit as lifelessly austere as it sounds. We are hearing that this will, among other things, raise the student-to-TA ratio in histcon by 25% next year.

But what is most important to grasp from these more recent struggles on a day like today is how profoundly difficult and disorienting the wildcat action, in particular, was for both those waging it and for faculty caught between us and the administration.

Bob, uniquely among faculty, took our action very seriously—no “clucking protective noises,” for instance, nor any condescension. He helped us understand our strategic leverage, and identify the underlying importance of our cause. This was, in his understanding, that we were challenging, in the context of a labor action, the very circumscription of worker demands to consumer goods by demanding to be on the upside of accumulating wealth in the California real estate market, despite being propertyless.

Or, as Melinda Cooper puts it, in the concluding passages of her new book, Counterrevolution:

The recent demands by the wildcat strikers at UC Santa Cruz for wage rises equal to soaring house prices in coastal California are case in point: by articulating what is at present impossible–that wages be indexed to asset price inflation–such actions threaten the basic hierarchy between capital and wage income and strike at the heart of our contemporary capitalist regime.

Without, perhaps, going quite as far as this, Bob gave us this analysis in real time precisely as our labor action, as he also taught us, pinched a chokepoint that instructors possess over the university’s highly financial form of accumulation. This is the threat we might pose to the flow of grades into future enrolments, and therefore student loans receipts, and therefore, in a long chain, bond ratings. It’s worth remarking that no grad was ever fired for empty class rooms—only missing grade rosters.

My experience of the strike, moreover, was very different from the majority of my coworkers, whose advisors and instructors, for reasons pure and otherwise, sought to talk them down from the action: to avoid the risk of firing, to stop asking for so much—or, who, it must be said, proactively found ways to submit grades against the will of strikers. Bob had no issue with my participation in the strike, as both his advisee and as the TA holding all his grades, assured that his students would eventually receive the grades they deserved.

And when the hammer came down from then-UC president (and former Homeland Security director) Janet Napolitano, Bob called me up for a long discussion. He made no attempt to persuade me against honoring the collective decision of strikers to defy the deadline, notwithstanding my visa situation. Instead, he communicated his understanding of my position, and described his own experience facing the draft in 1968.

In this, from my perspective, Bob distinguished himself among UC faculty, perhaps as something like a justice-seeking subject, in his terms. What seems indisputable to me, in any case, is that when Bob studied UC’s finances, or when he observed our strikes, “he could,” in Thompson’s words, “no longer, by his silence, assist in the mystification of the very institution in which he and his students work. He [came] to the side of the students by telling them what he knows of the truth.”

It’s a lesson, and a responsibility, for all university workers. I am thankful that I was able to learn it from Bob, from his instruction and by his example.